Redefining & Investing in Community: Improving Telehealth Care and Educational Programs among People Incarcerated in Rural State Prisons

1. Significance

1A. Our proposed project targets three NIH-designated populations experiencing health disparities in the U.S. These include racial and ethnic minority groups (primarily people who identify as Black), people with lower socioeconomic status, and people incarcerated and those working in carceral settings in rural communities. We are prioritizing these populations because they are among the populations most impacted by the carceral system. Moreover, although people in the carceral system are not an NIH-designated population experiencing health disparities per se, they are a vulnerable group who are often overlooked in health research and as per NIH’s health disparity definition, experience a higher incidence of unmet health needs, disease, and risk factors for disease. These disparities among incarcerated individuals were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting the need for increased attention to members of these communities. In doing so, prioritizing work that is community-driven is key.

1B. Approximately 70% of prisons in the U.S. are located in rural communities. Due to inequitable education, economic disparities, and other social determinants, there are persistent health disparities experienced by people residing in rural geographic regions of the U.S., including reduced mortality. In rural communities, there is reduced healthcare access and reduced access to intensive care. For example, hospitals serving rural communities have limited intensive care unit beds and infrastructure. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded such limitations, leaving rural communities more vulnerable to iatrogenic outcomes from COVID-19. Telehealth is one mechanism that can provide effective and efficient healthcare services to rural communities. Increased educational access could also improve information to promote preventative health seeking and critical thinking about (and participation in) health behaviors. Accordingly, the criminal legal system reflects a fertile ground for reducing health disparities.

Partner Site 1: Maryland. In December 2020, there were 15,623 individuals incarcerated in Maryland across 24 state prisons, private prisons and local jails. Maryland had a budget of ~$842 million to operate these facilities. Approximately 67% of state-run prisons (12 of the 18) in Maryland are located in rural areas. Black and Brown people are overrepresented in these settings. Data from 2019 demonstrated a positive association between incarceration and chronic illnesses. Despite the well-established correlations between incarcerated populations and poverty, incarcerated people in the state of Maryland are required to make a copay during their incarceration. Additionally, there is a healthcare coverage insecurity gap upon release from prison and approximately 90% of returning citizens leave prison without coverage. Moreover, healthcare disparities are not limited to incarcerated populations. For example, in a 2019 survey of correctional officer mental health, nearly 20% of correctional facility employees exhibited PTSD symptoms suggesting the need for increased mental health care coverage.

Partner Site 2: Missouri. In December 2020, there were 23,062 individuals incarcerated in Missouri in 21 state prisons, private prisons or local jails. Missouri had a budget of ~$790 million to operate these facilities. Similar to Maryland, there are significant disparities in incarceration as it relates to Black and Brown individuals. Missouri has 93 of 115 counties (81%) that are classified as rural. Recent data indicate the highest rates of prison admissions in Missouri are in rural counties; likewise, most state prisons are located in rural counties in Missouri. Missouri already has limited telehealth services offered in prisons and correctional facilities. However, mental health services via telehealth are nonexistent and it is unclear whether general telehealth services are available across facilities and if so, the logistics of access for people who are incarcerated. Moreover, correctional officer staff experience similar issues with mental health; 2020 data suggests that 33% of these officers have depression.

1C. The proposed project aims to increase access to health care services and improve and sustain higher educational pursuits among people incarcerated and those working within carceral systems. This could promote health and well-being for most marginalized populations, extend public health efforts, and provide savings to taxpayers and healthcare systems (e.g., ERs). Additionally, it could help reduce the burden on DOCs to provide comprehensive services needed; DOCs are poorly situated to provide certain types of support. Our proposed structural intervention could prepare incarcerated individuals to be engaged in a robust workforce upon reentry, meeting workforce needs in the broader economy. Finally, the posited intervention aims to address the mental health care needs of correctional officers within the DOC landscape.

1B. Approximately 70% of prisons in the U.S. are located in rural communities. Due to inequitable education, economic disparities, and other social determinants, there are persistent health disparities experienced by people residing in rural geographic regions of the U.S., including reduced mortality. In rural communities, there is reduced healthcare access and reduced access to intensive care. For example, hospitals serving rural communities have limited intensive care unit beds and infrastructure. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded such limitations, leaving rural communities more vulnerable to iatrogenic outcomes from COVID-19. Telehealth is one mechanism that can provide effective and efficient healthcare services to rural communities. Increased educational access could also improve information to promote preventative health seeking and critical thinking about (and participation in) health behaviors. Accordingly, the criminal legal system reflects a fertile ground for reducing health disparities.

Partner Site 1: Maryland. In December 2020, there were 15,623 individuals incarcerated in Maryland across 24 state prisons, private prisons and local jails. Maryland had a budget of ~$842 million to operate these facilities. Approximately 67% of state-run prisons (12 of the 18) in Maryland are located in rural areas. Black and Brown people are overrepresented in these settings. Data from 2019 demonstrated a positive association between incarceration and chronic illnesses. Despite the well-established correlations between incarcerated populations and poverty, incarcerated people in the state of Maryland are required to make a copay during their incarceration. Additionally, there is a healthcare coverage insecurity gap upon release from prison and approximately 90% of returning citizens leave prison without coverage. Moreover, healthcare disparities are not limited to incarcerated populations. For example, in a 2019 survey of correctional officer mental health, nearly 20% of correctional facility employees exhibited PTSD symptoms suggesting the need for increased mental health care coverage.

Partner Site 2: Missouri. In December 2020, there were 23,062 individuals incarcerated in Missouri in 21 state prisons, private prisons or local jails. Missouri had a budget of ~$790 million to operate these facilities. Similar to Maryland, there are significant disparities in incarceration as it relates to Black and Brown individuals. Missouri has 93 of 115 counties (81%) that are classified as rural. Recent data indicate the highest rates of prison admissions in Missouri are in rural counties; likewise, most state prisons are located in rural counties in Missouri. Missouri already has limited telehealth services offered in prisons and correctional facilities. However, mental health services via telehealth are nonexistent and it is unclear whether general telehealth services are available across facilities and if so, the logistics of access for people who are incarcerated. Moreover, correctional officer staff experience similar issues with mental health; 2020 data suggests that 33% of these officers have depression.

1C. The proposed project aims to increase access to health care services and improve and sustain higher educational pursuits among people incarcerated and those working within carceral systems. This could promote health and well-being for most marginalized populations, extend public health efforts, and provide savings to taxpayers and healthcare systems (e.g., ERs). Additionally, it could help reduce the burden on DOCs to provide comprehensive services needed; DOCs are poorly situated to provide certain types of support. Our proposed structural intervention could prepare incarcerated individuals to be engaged in a robust workforce upon reentry, meeting workforce needs in the broader economy. Finally, the posited intervention aims to address the mental health care needs of correctional officers within the DOC landscape.

2. ComPASS Team

2A. Project Leaders

Jacob Eikenberry, MSW (MPI, Multi Principal Investigator) is an Assistant Professor in the Master of Social Work program at Colorado Mesa University and a doctoral candidate (2023) in Social Work at Saint Louis University. Mr. Eikenberry is also the Director of Research and Evaluation at Prison to Professionals (P2P).

Machli Joseph, Ed.D. (MPI) is the Director of Policy, Advocacy, and Outreach at P2P.

Stanley Andrisse, Ph.D., MBA (Co-Investigator) is an Assistant Professor at Howard University College of Medicine and the Founder and Executive Director of P2P.

Rebecca Fix, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health within the Department of Mental Health. She is also a licensed clinical psychologist.

2B. Community Partners and Consultants in Maryland

Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services (DPSCS): We aim to partner with the DPSCS to connect incarcerated populations with access to additional and supplementary physical and mental health care services during their incarceration via telehealth services through health care professionals across the State. Additionally, we hope to connect these populations with increased college and career readiness programming, and other comprehensive supports that assist incarcerated populations in building capital related to their success post-incarceration (e.g., P2P,, and Light to Life programming). Within this, we also aim to coordinate on providing an appropriate (i.e., confidential) space for telehealth program use; online and hybrid course participation; and partner in recruiting requisite participants for telehealth and course participation.

Light to Life: Builds a connection to the community with healing justice approaches in the movement to prevent gender-based violence among incarcerated women.

2C. Community Partners and Consultants in Missouri

Missouri Department of Corrections (MODOC): We aim to partner with the Missouri DOC to provide the same or similar services listed above with DPSCS, utilizing community partners that work in Missouri.

Healthy Routines: Aims to connect individuals currently incarcerated or formerly incarcerated to higher educational opportunities, employment, and adequate housing.

St. Patrick Center: Transforms lives and works to create a community where everyone has access to sustainable housing, employment, and healthcare.

Jacob Eikenberry, MSW (MPI, Multi Principal Investigator) is an Assistant Professor in the Master of Social Work program at Colorado Mesa University and a doctoral candidate (2023) in Social Work at Saint Louis University. Mr. Eikenberry is also the Director of Research and Evaluation at Prison to Professionals (P2P).

Machli Joseph, Ed.D. (MPI) is the Director of Policy, Advocacy, and Outreach at P2P.

Stanley Andrisse, Ph.D., MBA (Co-Investigator) is an Assistant Professor at Howard University College of Medicine and the Founder and Executive Director of P2P.

Rebecca Fix, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health within the Department of Mental Health. She is also a licensed clinical psychologist.

2B. Community Partners and Consultants in Maryland

Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services (DPSCS): We aim to partner with the DPSCS to connect incarcerated populations with access to additional and supplementary physical and mental health care services during their incarceration via telehealth services through health care professionals across the State. Additionally, we hope to connect these populations with increased college and career readiness programming, and other comprehensive supports that assist incarcerated populations in building capital related to their success post-incarceration (e.g., P2P,, and Light to Life programming). Within this, we also aim to coordinate on providing an appropriate (i.e., confidential) space for telehealth program use; online and hybrid course participation; and partner in recruiting requisite participants for telehealth and course participation.

Light to Life: Builds a connection to the community with healing justice approaches in the movement to prevent gender-based violence among incarcerated women.

2C. Community Partners and Consultants in Missouri

Missouri Department of Corrections (MODOC): We aim to partner with the Missouri DOC to provide the same or similar services listed above with DPSCS, utilizing community partners that work in Missouri.

Healthy Routines: Aims to connect individuals currently incarcerated or formerly incarcerated to higher educational opportunities, employment, and adequate housing.

St. Patrick Center: Transforms lives and works to create a community where everyone has access to sustainable housing, employment, and healthcare.

3. Structural Intervention: Programming and Research

Planning Process

In brief, the P2P program aims to provide internet access to 14 prisons in two states (7 in Maryland, 7 in Missouri) to promote health equity among people who are transitioning out of the carceral system (beginning programming 1 year prior to participants’ release and 1 year following their release) by providing the tools, programming, resources, and social capital needed to promote health equity and excel in higher education. The intervention was developed to increase health care access, education, and preventative health behaviors. Tools include increased access to healthcare through provided telehealth services both when individuals are within the carceral system (and have 1 year or less until their scheduled release) and providing access to telehealth when individuals are released, programming, and resources will lead in the long-term to increased employment opportunities, income, preventative health behaviors, and health outcomes. We will accomplish these aims by integrating two new structural-level interventions into our practice for people within the carceral system: (1) high-speed internet access that will afford access to telehealth for physical and mental health care access and (2) new online P2P higher education and mental health courses. We will support implementation of high-speed broadband internet access in state-level prisons in MD and MO.

3A. Structural Factors for Potential Intervention

Within this section, we review core components of our proposed structural intervention. In addition to increasing telehealth accessibility, internet access will also grant access to P2P mentoring and health-promoting courses.

3Ai. Set up High-Speed Internet Access for Physical and Mental Health Care Access

We hope to provide participants with access to telehealth in prisons within the states of Maryland and Missouri. Physical and mental telehealth services may be provided in either a dedicated healthcare space within the prison (e.g., nurses office) or another dedicated private space that the facility can provide. Success will be measured through the number of sites at which we set up high-speed internet as well as with use of the newly dedicated spaces for accessing telehealth services made possible through high-speed internet access.

3Aii. Physical and Mental Health Care Access for Correctional Officers

We anticipate making services available to prison staff within facilities and to provide blueprints to prison staff that guide them toward access to physical and mental health care.

3Aii. Continued Internet Access Upon Release

We will provide participants with a cell phone and a 15 GB data plan for 1 year following their release. Participants will be able to access physical and mental health services through these phones. We will measure success in continued telehealth (or other physical or mental health care access) through examination of participants’ EMA responses. We will prioritize recruitment of rural and Black people being released from prisons to promote health equity.

Telehealth services are available but limited in different ways within the target regions. We anticipate our internet expansion will allow incarcerated populations to connect with telehealth services, including patient or professional education, in addition to telemedicine (i.e., provision of clinical services). We further anticipate people in carceral settings having access to videoconferencing for real-time consultations, visitation even during periods of quarantine, and educational videos. In addition to these health-promoting resources, we will develop higher education and mental health education courses or other educational materials

3B. Existing and New Online P2P Resources: Mentoring and Health-Promoting Courses

3Bi. Existing P2P Mentoring

Individuals who apply and are accepted into the P2P Scholar program (who are required to be actively incarcerated or have a history of incarceration to enroll) are provided with a support team to assist them on their educational and career journey. Each participating scholar is assigned one tutor and one peer-mentor. Tutors serve as educational accountability partners and peer mentors serve as criminal legal system and life accountability partners. Tutors and peer-mentors receive extensive training in the use of appropriate language (e.g., person-first, systems-first, avoiding stigmatizing language), the asset-based community development model, and cultural sensitivity. In addition to these training sessions, peer-mentors complete additional coursework in trauma-informed care, peer-coaching techniques, and guidelines for mentoring interactions.

In the proposed study, success in mentoring engagement will be measured in the number of applications for the cohort and acceptances within the next cohort who identify with our target demographic priorities (i.e., rural, Black). To best promote health equity, our project funding will be dedicated to new cohort applicants who identify as from a rural community and identify as Black.

3Bii. Existing P2P Education Courses

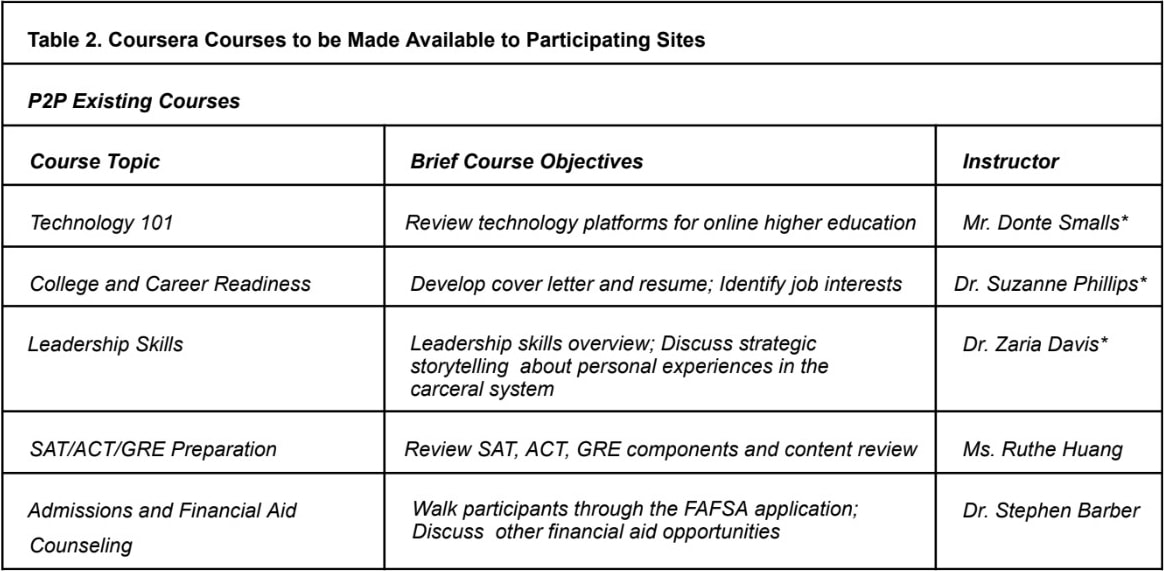

P2P has a series of courses they provide that are administered quarterly at a minimum (2017-present). In addition to the workshop sessions, participating scholars are given assignments to complete within one week. P2P also connects those it serves to the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network, a community-based partner of P2P, for opportunities to attend speaker seminars relevant to educational success and career development. Table 2 below provides an overview of existing and new curriculum content.

For all existing and new P2P courses, success will be measured in the number of participants who matriculate through each course with a focus on people who identify as from a rural and/or Black community. We will primarily serve individuals with these demographic characteristics within the prisons we have selected in the states of Maryland and Missouri.

3A. Structural Factors for Potential Intervention

Within this section, we review core components of our proposed structural intervention. In addition to increasing telehealth accessibility, internet access will also grant access to P2P mentoring and health-promoting courses.

3Ai. Set up High-Speed Internet Access for Physical and Mental Health Care Access

We hope to provide participants with access to telehealth in prisons within the states of Maryland and Missouri. Physical and mental telehealth services may be provided in either a dedicated healthcare space within the prison (e.g., nurses office) or another dedicated private space that the facility can provide. Success will be measured through the number of sites at which we set up high-speed internet as well as with use of the newly dedicated spaces for accessing telehealth services made possible through high-speed internet access.

3Aii. Physical and Mental Health Care Access for Correctional Officers

We anticipate making services available to prison staff within facilities and to provide blueprints to prison staff that guide them toward access to physical and mental health care.

3Aii. Continued Internet Access Upon Release

We will provide participants with a cell phone and a 15 GB data plan for 1 year following their release. Participants will be able to access physical and mental health services through these phones. We will measure success in continued telehealth (or other physical or mental health care access) through examination of participants’ EMA responses. We will prioritize recruitment of rural and Black people being released from prisons to promote health equity.

Telehealth services are available but limited in different ways within the target regions. We anticipate our internet expansion will allow incarcerated populations to connect with telehealth services, including patient or professional education, in addition to telemedicine (i.e., provision of clinical services). We further anticipate people in carceral settings having access to videoconferencing for real-time consultations, visitation even during periods of quarantine, and educational videos. In addition to these health-promoting resources, we will develop higher education and mental health education courses or other educational materials

3B. Existing and New Online P2P Resources: Mentoring and Health-Promoting Courses

3Bi. Existing P2P Mentoring

Individuals who apply and are accepted into the P2P Scholar program (who are required to be actively incarcerated or have a history of incarceration to enroll) are provided with a support team to assist them on their educational and career journey. Each participating scholar is assigned one tutor and one peer-mentor. Tutors serve as educational accountability partners and peer mentors serve as criminal legal system and life accountability partners. Tutors and peer-mentors receive extensive training in the use of appropriate language (e.g., person-first, systems-first, avoiding stigmatizing language), the asset-based community development model, and cultural sensitivity. In addition to these training sessions, peer-mentors complete additional coursework in trauma-informed care, peer-coaching techniques, and guidelines for mentoring interactions.

In the proposed study, success in mentoring engagement will be measured in the number of applications for the cohort and acceptances within the next cohort who identify with our target demographic priorities (i.e., rural, Black). To best promote health equity, our project funding will be dedicated to new cohort applicants who identify as from a rural community and identify as Black.

3Bii. Existing P2P Education Courses

P2P has a series of courses they provide that are administered quarterly at a minimum (2017-present). In addition to the workshop sessions, participating scholars are given assignments to complete within one week. P2P also connects those it serves to the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network, a community-based partner of P2P, for opportunities to attend speaker seminars relevant to educational success and career development. Table 2 below provides an overview of existing and new curriculum content.

For all existing and new P2P courses, success will be measured in the number of participants who matriculate through each course with a focus on people who identify as from a rural and/or Black community. We will primarily serve individuals with these demographic characteristics within the prisons we have selected in the states of Maryland and Missouri.

3Biii. New P2P Courses and Consultation

We propose to develop eight new courses or materials to educate people incarcerated or working in prisons in Maryland and Missouri. These include topics such as: (1) Stigma and Health Care (Including Mental Health), (2) Mental Health 101, (3) Treatment for Mental Disorders, (4) Substance Use 101, (5) Coping Skills, (6) Healthy Masculinity, (7) Media Literacy, (8) Exercise and Nutrition in Prisons.

Treatment for Mental Disorders; Substance Use 101; Coping Skills

We hope to collect data through three methods. First, we hope to collect data from people in carceral systems and staff via self-report surveys at two timepoints (approximately 1 year apart). Second, we will collect EMA data from formerly incarcerated people upon their release for 1 year. Third, we will collect qualitative data through individual interviews with formerly incarcerated persons at up to two timepoints (4-6 months apart) and through individual interviews with staff at a single time point. We anticipate focusing on two categories of physical and mental health outcomes for this proposed project

– health care access and health care usage. The first overarching outcome we will measure is proximal

– increased health care access and engagement (through telehealth). We hope to see increased

access to medication, mental health care services, and preventative care. We will test for equity in health care usage by comparing monthly usage rates with monthly population representation within the facility. For these analyses, we will use prison-level data from each participating site to acquire timely (by month) data. Data on population rates and rates of physical and mental telehealth care usage to calculate ratios (relative to representation within a given prison) will all come from the prison. See Table 3 for more details on survey study measures and Table 4 for EMA questions.

Table 3. Structural Intervention Survey Study Measures |

Carceral System-Specific Health Care Access and Usage |

Resource Use. We hope to obtain a detailed log of who requests and receives physical (i.e., PCP, specialist) and mental telehealth resources including demographic information (age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, years incarcerated, offense category) facility in which they are incarcerated, and county of origin. |

Features of Health Care Use. We hope to receive monthly reports of aggregate health care outcomes including: prescribed medication (with a subcategory of psychotropic medication prescriptions), PCP appointments, appointments with medical specialists, mental health care services, and preventative care. |

Community-Specific Health Care Access and Usage |

Insurance access. Assess for health insurance and whether it is through a private or governmental provider. |

Resource Use. We will inquire about physical (i.e., PCP, specialist) and mental telehealth resources, including: whether they accessed resources, what types of providers they met with (broadly), whether they were prescribed medication, whether they take the medications as prescribed, whether they receive other recommendations from their doctor (e.g., diet changes), and whether they adhered to those. |

Features of Health Care Use. We will ask about health care outcomes including: satisfaction with health care services, whether appointments were via telehealth or in-person, barriers to accessing health care, and preventative care. |

Course Participation Outcomes |

Resource Use. We will have a count of how many incarcerated individuals and staff view online videos of our course content (when logging on/upon signing up as a ‘CAPTCHA', we will ask for viewer role (incarcerated person or staff), gender identity, race, and ethnicity. |

General Self-Efficacy Scale –Care Access. Modified 6 items assess self-efficacy to access health care; α = .79-.88 |

Stigma about Physical and Mental Health Care. We will use the Perceptions of Stigmatization by Others for Seeking Help (PSOSH Scale) to measure stigma specific to seeking physical and mental health services. This is a 5-item Likert scale questionnaire (1=not at all to 5=a great deal); (α =.94). |

Attitudes toward Physical Health Care. To measure whether participants are amenable to physical health care, the Care Access measure will be used. This includes six items specific to whether and when someone might be willing to seek out physical health care 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); (α =.79). |

Openness to Mental Health Care. To measure whether participants are amenable to counseling, the Openness to Counseling Services will be used. This includes five items specific to reasons someone might be willing to seek out mental health care (0 = not at all to 3 = very likely); (α =.96). |

Course-Specific Knowledge. For each course, we will have a pre-immediate post questionnaire including to assess knowledge. We will use psychometrically validated measures whenever possible. |

Media literacy. We will use the Knowledge of Media Effects scale to measure whether participants believe that media affects them. It is a 3-item, 7-point (1 = agree to 7 = disagree) Likert scale (α = .70). |

Gender Expectations and Conformity. The Comfort and Conformity of Gender Expression Scale (α = .88). |

Coping. We will use a modified version of the Coping Strategies Indicator, which includes 33 items with presented response options on three-point Likert scale (three subscales α = .73 to .90). |

Stress from Incarceration. We will use a modified version of the Perceived Stress Scale to assess stressors (α = .77). |

Staff Outcomes |

Stigma about Physical and Mental Health Care. We will use the Perceptions of Stigmatization by Others for Seeking Help (PSOSH Scale) to measure stigma specific to seeking physical and mental health services. This is a 5-item Likert scale questionnaire (1=not at all to 5=a great deal); (α =.94). |

Attitudes toward Physical Health Care. To measure whether participants are amenable to physical health care, the are Access measure will be used. This includes six items specific to whether and when someone might be willing to seek out physical health care 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); (α =.79). |

Openness to Mental Health Care. To measure whether participants are amenable to counseling, the Openness to Counseling Services will be used. This includes five items specific to reasons someone might be willing to seek out mental health care (0 = not at all to 3 = very likely); (α =.96). |

Course-Specific Knowledge. For each course, we will have a pre-immediate post questionnaire including knowledge-based items specific to the course content. |

Prison culture. We will use the Prison Organizational Culture Assessment. This is 18-Likert scale style items (α =.87). |

General Self-Efficacy Scale –Care Access (Romppel et al., 2013). Modified 6 items assess self-efficacy to access health care; (α = .79-.88). |

Coping. We will use a modified version of the Coping Strategies Indicator, which includes 33 items with presented response options on three-point Likert scale (three subscales α = .73 to .90). |

Workplace Stress. We will use the Work Stress Scale for Correctional Officers to assess stressors specific to their environment (α = .94) |

Individual interviews with formerly incarcerated individuals will inquire about the efficacy and effectiveness of the structural intervention, and whether and how the individual noticed changes in their healthcare access and physical and mental health. It will also include a section for barriers to care and recommendations for improving practices and policies. We will also ask about Coursera and P2P content, with a specific prompt about the P2P mentoring program. Finally, interviews will provide a substantial portion of the individuals’ time to ask about their reentry process and difficulties navigating healthcare prior to and after their release.

Table 4. EMA Measurement of Health Care and Associated Behaviors |

Question Content |

In the past 2 weeks: (1): How has your physical health been? Poor, Somewhat poor, Okay, Somewhat good, Good |

(2): How has your sleep been? |

(3): How has your stress level been? |

(4): How has your mood been? |

(5): What health promotion behaviors have you done? (Check all that apply) Exercised, Ate healthy most of the time, Spent time with family, Spent time with friends, Went to a religious service or event, Avoided substance use (e.g., nicotine, alcohol, other drugs) |

(6): Have you met with someone using telehealth services in the past 2 weeks? (Yes): With which type of health specialist did you meet? (Check all that apply) Primary care, Physical health specialist (e.g., nephrologist, infectious disease expert), Mental health, Dentist, Eye doctor (opthamologist) (No): Why not? (Check all that apply) No need, Insurance problems, It didn’t seem necessary, Other ____________ |

(7): Do you have health insurance? Yes – private, Yes – government (Medicare), No – I want someone to contact me and help me get connected to insurance, No – I do not want to be contacted to get connected to insurance |

Individual interviews with prison staff will primarily inquire about procedural efficacy in implementing the structural intervention and their own access to care and education. We will also promote discussion about recommendations for sustaining the structural intervention, barriers to implementation, and recommendation for policies and practices moving forward. Finally, staff will be provided the opportunity to talk about their own healthcare needs and barriers to accessing physical and mental health care.

Potential participant reach of the structural intervention within Maryland and Missouri We are partnering with the Department of Corrections in both Maryland and Missouri. Our collective goal is to set up (or improve) high speed internet access in 7 facilities within each state over the course of the project period (14 in total). This will afford us the opportunity to ultimately expand access to telehealth care services in multiple state prisons at each of the sites, particularly as we begin rolling out and troubleshooting internet access in these sites. Because state prisons are in locations spanning much of Maryland and Missouri, we anticipate this intervention and partnership has potential to reach prospective participants incarcerated in all 38 prisons (within Maryland (n = 18) and Missouri (n = 20) combined). Altogether, this intervention has the capacity to impact approximately 40,000 individuals (not counting staff) who are incarcerated in those facilities, the majority of whom are Black.

High-speed internet access is being funded by the federal government in select rural areas of the U.S. because they “need high-speed internet to run their businesses, go to school and connect with their loved ones.” We want to ensure that people who are incarcerated – who are among the most underserved and vulnerable populations in the U.S. – have comparable access to internet and resources that are even more pressing to improve their healthcare access and reduce health disparities. And we believe that the intervention we are proposing can help achieve that goal.

3C. Giving Participants a Voice in Program Design, Implementation, and Evaluation

Development of interventions, and program evaluations should involve those who are directly impacted. Therefore, we will recruit 15 formerly incarcerated persons in each state and 15 prison staff from each state (working to obtain representation from each affiliated facility within both Maryland and Missouri) to develop two Prison Health Care Advisory Boards (Formerly Incarcerated and Administration and Staff PH-CABs), ensuring we have individuals representing rural communities who are predominantly (or exclusively) Black. PH-CAB members will be paid for their time. We will rely on our ability to meet on site with prospective members for recruitment and retention of these members. Dr. Andrisse and P2P has a working relationship with the Department of Corrections administration team in both Maryland and Missouri, and with multiple community partners in each state. Collaborators promote data-driven, collaborative structural initiatives to provide resources to promote health equity among children, families, and communities and also work with leadership in multiple contexts to catalyze organizing efforts and resources. Each has committed to helping us recruit PH-CAB members.

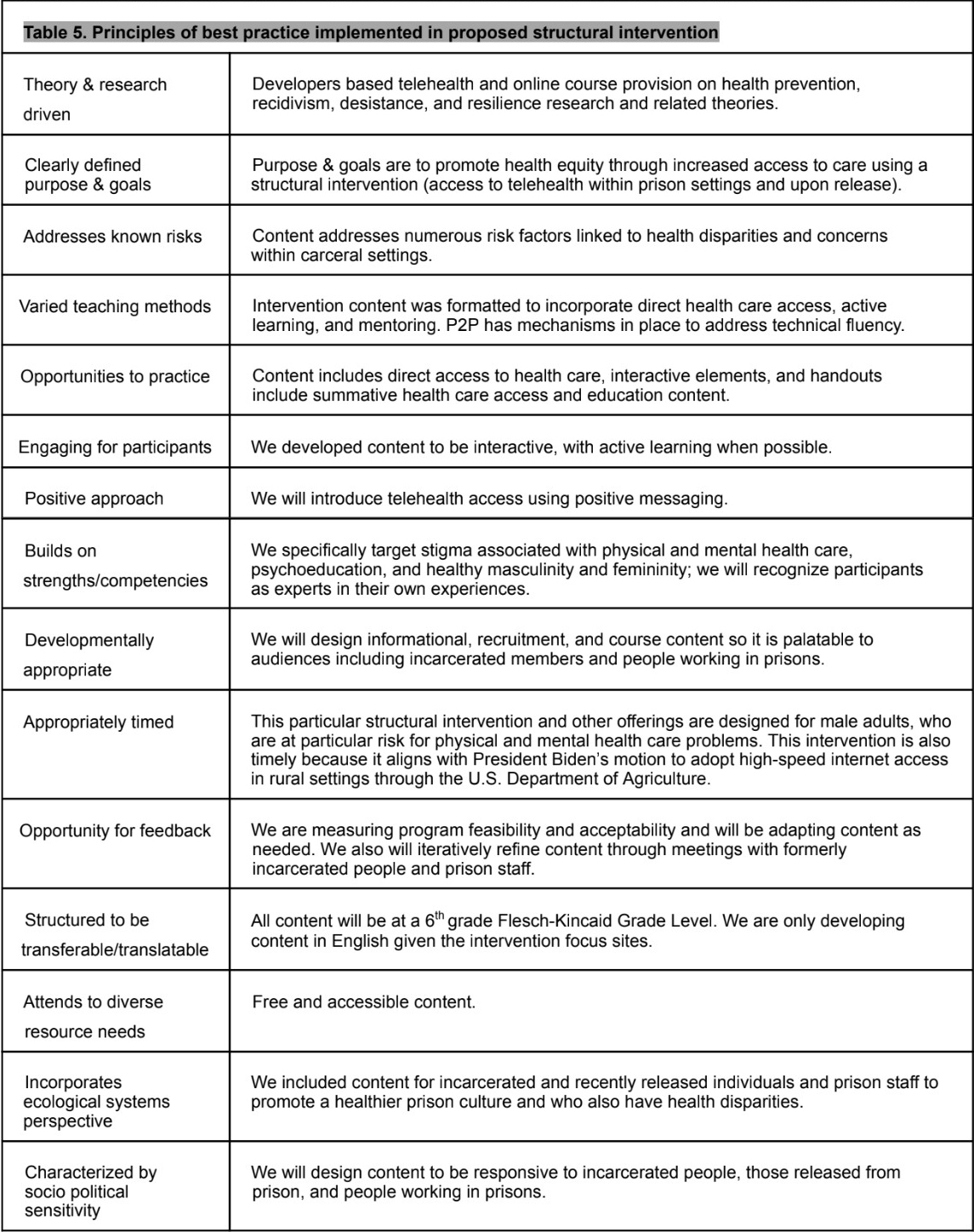

The PH-CAB will meet with the project team bimonthly, primarily through conference calls and Zoom calls (but also in-person annually at a minimum) to inform the initial intervention content, to iteratively refine the course content and affiliated recruitment and handout materials, to inform study survey wording and content, and to assist with program promotion materials and distribution. The last piece of promoting materials is key to the success of our program, for people who are incarcerated and staff alike. Our structural intervention and associated programming were designed to incorporate best practices. Table 5 below lists the 15 principles of effective prevention. We will use these principles to guide conversations with PH-CAB members focused on refining intervention content.

In addition, once data are collected and analyzed, members of both the incarcerated and staff PH CABs will be invited to a meeting during which study findings will be discussed and interpreted. Finally, they will be invited to collaborate on targeted practice briefs that will be disseminated through printed handouts for incarcerated people. For staff, materials will be disseminated through listservs, social media, and professional websites. Those who serve on the PH-CAB will be eligible to complete courses and participate in P2P’s mentoring program, but not to participate in the study. Finally, our community partners will help coordinate and co-lead conversations with PH-CAB members.

3D. Plans for Sustainability of Research Capacity and Structural Intervention Efforts

We will work with states to find funding to sustain internet access and telehealth services; we will develop a blueprint for the prison staff (particularly counselors given their role and also parole officers will have content developed specifically for them) in how to set up incarcerated people with insurance access upon their release. We will also develop a comprehensive list of resources for prisons to hand out to individuals upon their release for getting them set up with insurance, locating physical and mental health providers, and finding ways to access telehealth services locally (e.g., in libraries, technical schools). In addition, P2P will continue to provide free mentoring services and course offerings to the incarcerated people in states.

Bibliography

- Ahalt C, Binswanger IA, Steinman M, Tulsky J, Williams BA. Confined to ignorance: The absence of prisoner information from nationally representative health data sets. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(2):160-6.

- Wang EA, Zenilman J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Ethical considerations for COVID-19 vaccine trials in correctional facilities. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1031-2.

- Burki T. Prisons are “in no way equipped” to deal with COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1411-2.

- Johnson L, Gutridge K, Parkes J, Roy A, Plugge E. Scoping review of mental health in prisons through the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e046547.

- Berk J, Rich JD, Brinkley-Rubinstein L. What are the greatest health challenges facing people who are incarcerated? We need to ask them. The Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(10):e703-e4.

- Kluckow R, Zeng Z. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2020–Statistical Tables. In: Statistics BoJ, editor. https://bjs. ojp. gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus20st. pdf2022.

- World Population Review. Incarceration rates by country. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/incarceration-rates-by-country2022.

- Bronson J, Carson EA. Prisoners in 2017. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2019;500:400.

- Nellis A. The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons 2016.

- Pettit B, Gutierrez C. Mass incarceration and racial inequality. American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 2018;77(3-4):1153-82.

- Cloud DH, Parsons J, Delany-Brumsey A. Addressing mass incarceration: A clarion call for public health. American Public Health Association; 2014. p. 389-91.

- Gottfried ED, Christopher SC. Mental Disorders Among Criminal Offenders. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2017;23(3):336-46. doi: 10.1177/1078345817716180.

- Pettit B. Invisible men: Mass incarceration and the myth of black progress: Russell Sage Foundation; 2012.

- Eason JM. Prisons as panacea or pariah? The countervailing consequences of the prison boom on the political economy of rural towns. Social Sciences. 2017;6(1):7.

- Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Probst JC. Health care access in rural areas: Evidence that hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in the United States may increase with the level of rurality. Health & Place. 2009;15(3):761-70.

- Probst JC, Moore CG, Glover SH, Samuels ME. Person and place: The compounding effects of race/ethnicity and rurality on health. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1695-703.

- Topchik M, Gross K, Pinette M, Brown T, Balfour B, Kein H. The rural health safety net under pressure: Rural hospital vulnerability. Chicago, IL: Chartis Center for Rural Health, The Chartis Group. 2020.

- Hirko KA, Kerver JM, Ford S, Szafranski C, Beckett J, Kitchen C, Wendling AL. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020;27(11):1816-8.

- Feinstein L, Sabates R, Anderson TM, Sorhaindo A, Hammond C, editors. What are the effects of education on health? Measuring the effects of education on health and civic engagement: Proceedings of the Copenhagen symposium; 2006: OECD Paris, France.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-63. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30569-x.

- National Institute of Corrections. Maryland and Missouri 2020. In: Justice USDOJ. https://nicic.gov/state-statistics/2020/maryland-20202021.

- Prison Policy Initiative. The steep cost of medical co-pays in prison puts health at risk | Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/19/copays/. Note. Due to spacing restrictions, we were unable to fit all references on our bibliography page.